There are over 92,000 dams in the United States, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. They serve a variety of uses, including water storage, water management for the environment, hydroelectric generation, and recreation. Despite these differences in use, state-managed dams have one thing in common — they are old.

Large-scale dams such as the Hoover Dam, Glen Canyon Dam, and Oglala Dam were conceived in the golden era of infrastructure building, between the 1930s and 1960s. In thirty years, the Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built over 150 dams, just within the Colorado, Columbia, and Missouri River basins. Their construction was initiated to begin hydroelectric generation, to store high volumes of water for irrigation, or to calm strong river flows.

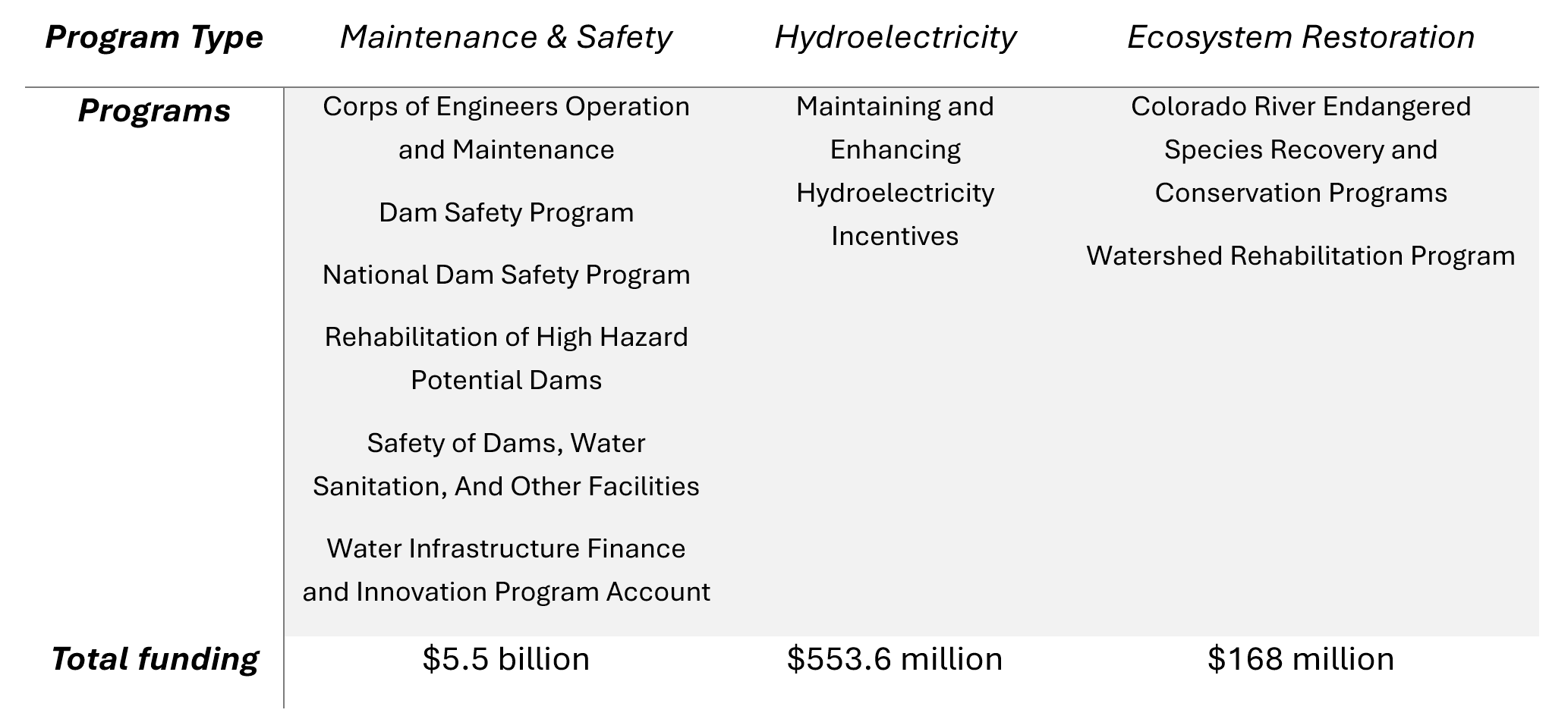

Since that bygone era, no comparable influx in federal funds to maintain, sustain, or evolve these behemoths of infrastructure. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) took a stab at rethinking our dam systems, largely in three focus areas: ecosystem restoration, hydroelectricity, and maintenance and safety (Table 1). Altogether, about $6.2 billion in federal dollars is eligible to be spent on dams; over $1.5 billion is discretely allocated for dam rehabilitation. About $3 billion of that figure has been awarded; details on the individual projects tracked by Water Program Portal can be found on the Outcomes Dashboard.

Table 1: Dam-Related Programs in IIJA

Two IIJA programs amounting to $168 million are focused on ecosystem restoration, with one $50 million bucket focused on the Colorado River Basin and the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program. The remaining$118 million is contained in the Watershed Rehabilitation Program. The program tasks the Natural Resources Conservation Service with providing updates to Department of Agriculture-assisted dams so that they may meet modern safety standards and extend their lifetimes.

Turning to hydroelectricity production, the approximately $554 million Maintaining and Enhancing Hydroelectricity Incentives program housed in the Department of Energy makes payments to private owners of dams. 65 percent of dams nationwide are privately owned, and this competitive grant program is open to those owned by commercial and industry interests and utilities. These payments focused on dam safety, environmental protection, and perpetuating resiliency in the dams’ connection to the larger grid.

Finally, six programs comprise about $5.5 billion in funding for dam maintenance and safety measures. The Corps of Engineers Operation and Maintenance program represents $4 billion of that pot, meant for the Army Corps to inspect its water-related infrastructure, including its dams. The other larger chunks in this section include the $585 million Rehabilitation of High Hazard Potential Dams program — for the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) to assign to pass on to states, where funding then goes toward non-governmental organizations to remediate unsafe dams — the $500million Bureau of Reclamation Dam Safety Program — for Reclamation to remediate its own dams — and the $200 million Bureau of Indian Affairs Safety of Dams, Water Sanitation, And Other Facilities program — to improve dams in Tribal Nations.

Overall, four percent of dams are federally owned, seven percent are state owned, and that ownership is split across several federal agencies, including those aforementioned. Almost all of the largest dams by volume are federal- or state-owned. This disparate dam management, in addition to the fact that many of these programs narrow in on making dams safe for the public, displays how federal management of these critical pieces of infrastructure has lagged, both when it comes to engineering and sociopolitical dynamics, these past few decades.

In the modern era, dams like the Rapidan Dam in Minnesota are at risk of collapsing. Others, like these two in Michigan and this one in Nebraska, breached due to new levels of extreme weather. Dams that are sited on Tribal lands are undergoing needed changes — from total removal like the Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River in California to the forestalling of new projects like this one on Navajo Nation land — to align local land management with Indigenous practices. Organizations like the Audubon Society are actively advocating for removal of dams for ecological reasons, like to restore the path of sea-run fish on the Kennebec River in Maine.

In 2023, 80 dams were removed. This year, others are looking to remove their hydropower functions, often for ecological reasons, or pursue total removal in favor of Indigenous land rights and local ecologies. On the opposite side of the coin, some dams in the West are being considered as important reservoirs for extra water in wet years, to be released in dry years. American dams, and the next few years will create precedents that will affect dam policy for decades to come.