The Klamath River Basin is a 12,000 square mile area hydrated by the 260-mile-long Klamath River, running from southern Oregon to northern California. Once upon a time, it was the third-largest salmon-producing region in the West, historically providing sustenance for the local Indigenous communities — namely the Hoopa, Karuk, Klamath, and Yurok tribes.

The area provides key ecosystem services. In addition to being an important rest stop for migratory birds flying the Pacific Flyway, the Klamath Estuary is a spawning ground for populations of Chinook and coho salmon as well as steelhead trout and other diverse endemic species. In 2019, the Yurok Tribe bestowed personhood on the Klamath River, giving it equivalent legal rights as a human and allowing the tribe to “bring a cause of action” against those harming its ecosystem.

Over the decades, water diversions and the hydroelectric dams on the Klamath have eroded water quality, decreased salmon runs, initiated toxic algae blooms, and even caused mass fish kills. One in 2002 decimated the region’s salmon populations, causing the deaths of an estimated 70,000 salmon, catalyzing years of local struggle to restore the Klamath.

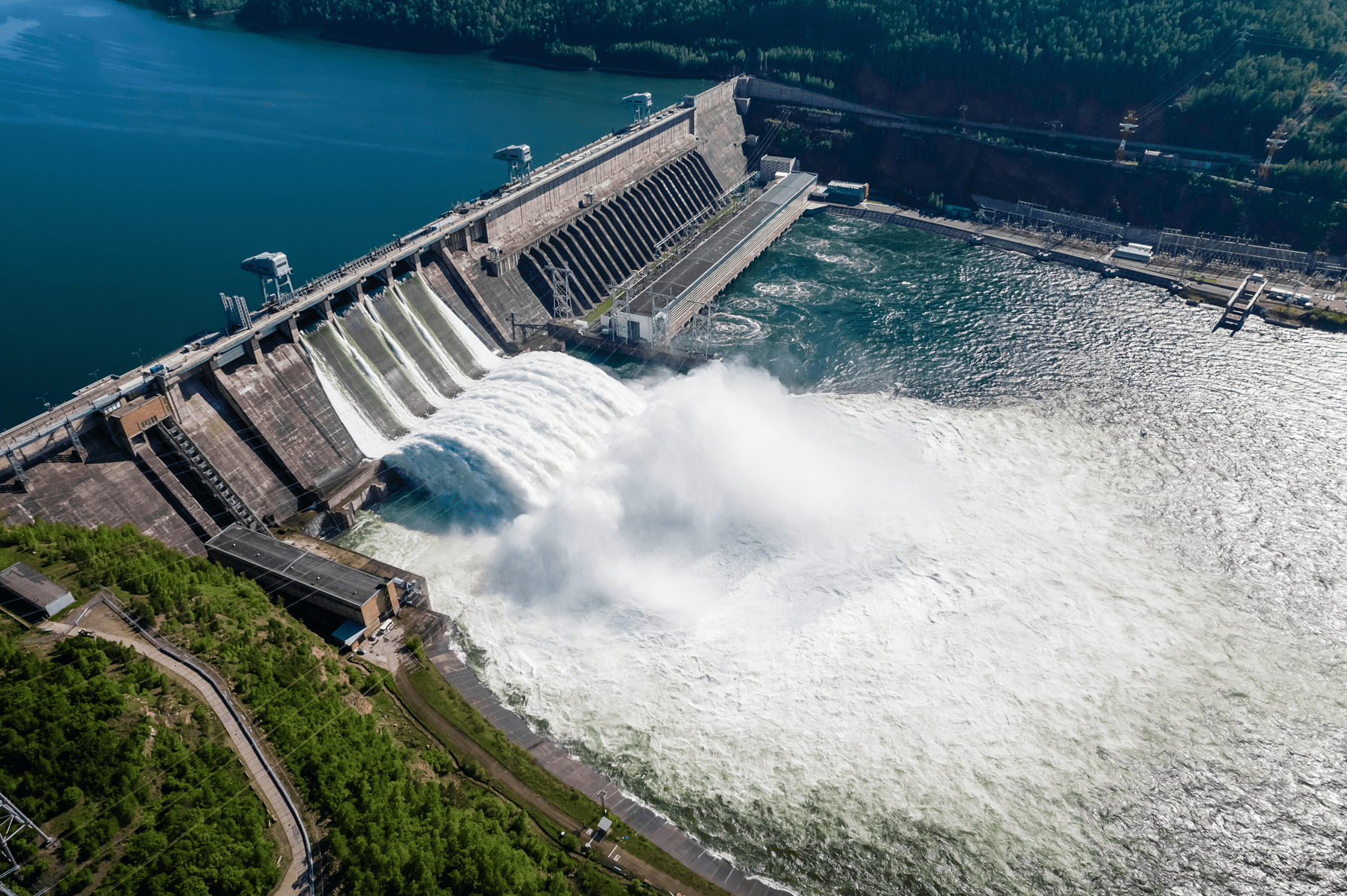

Seven dams were originally installed over the course of 60 years, ending in 1962, without tribal consultation. PacifiCorp is the Oregon-based utility that owns the dams and their hydroelectric generators, which had a peak generation capacity of 169MW. The 2002 mass kill initiated a series of protests, demonstrations, and elaborate negotiations that culminated in the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement. A coalition of local governments, tribal nations, conservation groups, and fishermen have advocated for the removal of the four lower Klamath River dams since 2002, with support ramping up in 2004 when PacifiCorp attempted to relicense those dams without including provisions or support for fish passage installation.

In 2022, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved the removal of the four dams. The dams should be removed before the 2024 salmon run and free up over 400 miles of river and stream habitats. As of now, one dam has been removed and the other three are slated for demolition in the next year.

The four dams were solely used to generate hydroelectricity, not to set aside water for residential or agricultural purposes. The project has a $450 million budget, raised by ratepayers for local utilities and a 2014 California proposition to clear up fish passages.

Removal of the dams represents the beginning of Klamath Basin ecosystem restoration. It will take about a decade for the ecosystem to bounce back, even with funding set aside in the project to restore over 2000 acres of reservoir bottom to its original state. Once steel and concrete are removed, blasts will be used to excavate accumulated sediment so that the dams’ water can be drained. Then, some 26 tons of seeds will be planted to revive native vegetation.

PacifiCorp analyzed the relative costs of adding fish ladders — sets of aquatic stairs that would allow salmon to swim upstream on their natural migratory pattern —versus removing the dams altogether and decided in favor of demolition. PacifiCorp noted that this removal would decrease the utility’s power generation by only 2 percent, a relatively minor change.

Local and state authorities have been preparing for ecosystem restoration. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife began collaborating with the Klamath Tribe in2021 to track young salmon born in hatcheries in order to examine how they navigate the basin. The department will release about 10,000 chinook salmon into two tributaries to sow the seeds for a new run of salmon originating in the Upper Klamath Basin.

IIJA also contains the Ecosystem – Klamath Basin program, which invests $162 million into supporting the resiliency of its ecosystem. Over the course of 2022, the Department of the Interior, the program’s funding agency, conducted a series of stakeholder engagement sessions with Indigenous communities in the basin, culminating in the program’s first round of awards in June 2022. The 32 funded ecosystem restoration projects included an expansion of the Klamath Falls National Fish Hatchery, funding to increase Yurok Tribal Capacity to restore the Lower Klamath River Basin, and other initiatives to improve the basin’s watershed, wetlands, and aquatic ecosystems.

Three other IIJA programs — Fish Passage, Ecosystem – Fish Passage, and Landscape Scale Restoration Water Quality and Fish Passage — and one IRA program — Tribal Climate Resilience: Fish Hatchery Operations and Maintenance — are making headway in restoring fish passages in key ecosystems nationwide. In total, they amount to $690 million in funding, of which about $205million has been awarded as of fall 2023.

A region bearing similar challenges to the Klamath is the Yakima River Basin in Washington. The Yakima River Basin Integrated Plan is a 30-year effort to ensure water resiliency while maintaining fish passages and fish habitats for the native populations of spring Chinook salmon and many species of trout. After historic lows of fish populations were witnessed in the early 1990s and persistent drought conditions in the early 2000s,

The plan was created in collaboration with the Yakama Nation, which also runs the Yakama Nation Fisheries that is attempting to reintroduce sockeye salmon to the basin and install a helix fish passage system at Cle Elum Dam. Again, it was grassroots action led by a tribal nation that has allowed for greater protection of a crucial ecosystem.

Over the past two years, the Yakama Nation has received almost $6.5 million in IIJA Fish Passage funding. There are a series offish passages on the Yakima River and its tributaries, mostly installed in1984 and 1985. This federal funding will go towards restoring several fish passages, removing dams, and develop databases for management of fish passages.

The expansion of federal funding for dam improvements and fish passages represents governmental recognition of these ecosystems’ importance for Indigenous traditions, fish populations, and bordering communities. Learn more about fish passage-related federal awards and open requests on the Water Program Portal.