Note: The dollar unit utilized in this digest is representative of the value of the dollar in 2005.

August 29th will be the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, one of the costliest natural disasters in American history, but in terms of lives lost and damages. Between 1,300 and 1,800 deaths have been attributed to the hurricane, as well as an estimated $125 billion to $320 billion in property damage. In this week’s digest, we remember the disaster and its impacts across the Gulf Coast — some of which persist to this day.

Katrina formed because of a tropical depression in the last week of August 2005 that moved across the Caribbean. On August 25th, the tropical storm gained strength until it was dubbed a hurricane, right before striking Florida. Hurricane Katrina then swept across the Gulf of Mexico, gaining strength all the way, until intensifying into a Category 5 hurricane on August 28th. Katrina lost a bit of strength before making landfall in Louisiana as a Category 3 hurricane, moving across the country before dissipating over Kentucky. A large amount of major damage was inflicted by Hurricane Katrina in eastern Louisiana, where New Orleans is located.

About 70 percent of New Orlean’s population was able to evacuate the city in anticipation of the hurricane. After the failures of the city’s levees, the majority of residents were evacuated, but not all — an estimated 60,000 people were trapped in the city, a little over half of which were rescued by the Coast Guard in the storm’s wake.

In New Orleans alone, over 200,000 homes were destroyed, about 70 percent of occupied units in the city. In total, more than a million people were temporarily displaced while about 600,000 households remained displaced a month after the hurricane in the climate resiliency disaster. Many of these damages occurred as a result of the failure of the city’s levees and the subsequent inundation of flooding. Power infrastructure was also hard hit, with more than three million customers left without power in the wake of the hurricane.

Billions in federal spending was dispersed to address the short-term emergency situation. About $120.5 billion was spent in total, with about $75 billion going solely to emergency relief such as short-term housing, food, and water. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) paid billions through the National Flood Insurance Program to Louisianian policy holders, amounting to about $10 billion. This supported roughly two-thirds of impacted New Orleans homeowners with flood insurance policies. Private insurance claims were able to cover under $30 billion in property damages.

While these figures are impressive in abstract, in reality it took a significant amount of time for resources to reach impacted communities, and even longer to begin rebuilding. This is partially illustrated by the population changes that occurred in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. A rapid population estimate from late January 2006 counted about 210,000 residents of the city, or over a third of the city’s inhabitants before the hurricane; this figure grew to about 223,000 in July 2006. The storm hit low-income and Black communities hardest, with specific zip codes suffering long-term economic losses. Plainly, those without the financial resiliency or resources to evacuate were left behind — communities that rely on public transit, families without a place to stay outside of the path of destruction, individuals without spare cash to spend. The same socioeconomic barriers limit these communities’ abilities to return to the city and rebuild.

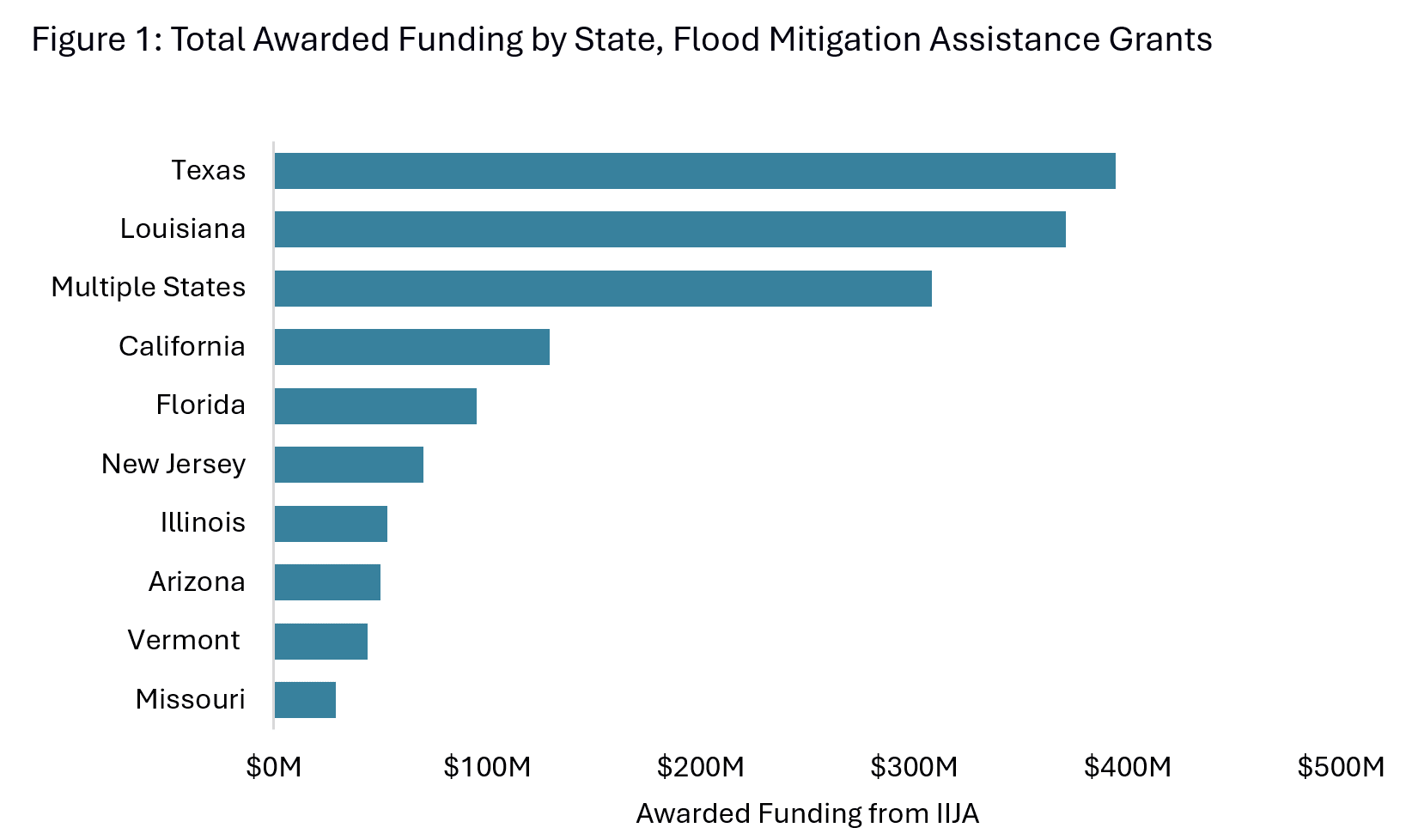

Together, the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) bolstered flooding funding to the tune of $27.5 billion, according to the Water Program Portal’s Opportunities Dashboard. $5 billion of that sum is allocated to FEMA, flowing from three IIJA programs: Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, Flood Mitigation Assistance Grants, and the Hazard Mitigation Grant programs. All three programs have been targeted by the Trump Administration in efforts to either cancel or reallocate their funding. $3.5 of the $5 billion increases funding for the Flood Mitigation Assistance Grants, which were originally authorized by the National Flood Insurance Act.

The competitive grant program has awarded about $1.9 billion for 394 projects according to the Outcomes Dashboard. The largest shares of total funding have gone to Texas ($394 million) and Louisiana ($371 million), as displayed in Figure 1. The highest per capita funding has gone to Louisiana ($81/capita). Generally, this funding has been awarded to state entities of emergency management or security, with the most federal funding supporting localized flood risk reduction projects; the majority of projects, however, support individual property mitigation projects.

Today, New Orleans looks different. Federal funding has improved 150 miles of levees, flood walls, gates, pumping stations, and other flood prevention and drainage solutions in the city via the $15 billion Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System. The 2020 census confirms a population loss of about 100,000 compared to 2000. Several communities are still undergoing rebuilding and revitalization efforts, for instance in the majority Black New Orleans East.

The resiliency of New Orleans in the 20-year wake of Hurricane Katrina is being commemorated widely. The City of New Orleans is hosting a suite of events in remembrance, museums and galleries across the city are exhibiting pieces about the disaster, and a youth art program has unveiled a new mural at the site of a levee breach. Finally, journalist Trymaine Lee — who has on the ground reporting on Hurricane Katarina 20 years ago — has released a documentary, “Hope in High Water: A People’s Recovery Twenty Years After Hurricane Katrina.” The documentary integrates community conversations, ongoing rebuilding efforts, and the first-hand accounts of those who experienced the hurricane in a narrative about New Orleans’s ongoing recovery.