The passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provide more than $150 billion to address underinvestment in the nation’s water infrastructure. But longtime underinvestment in physical infrastructure also means longtime underinvestment in the administrative infrastructure necessary to effectively apply for and then implement this federal funding.

To address this need, many IIJA and IRA programs contain set asides for technical assistance, generally cresting about two percent of total funding allocations. But sometimes more support from environmental financing professionals is needed to help entities — particularly those that have not historically accessed significant sums of federal funding — successfully build applications for funding. Enter: Environmental Finance Centers (EFCs).

In November 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced their selection of 29 EFCs. Over the course of five years, FY2022-FY2026, EPA stated it would distribute up to $150 million to these centers; $98 million of the dollars originate from IIJA’s funding for the Clean and Drinking Water State Revolving Loan Funds, with the remainder coming from annual EPA appropriations.

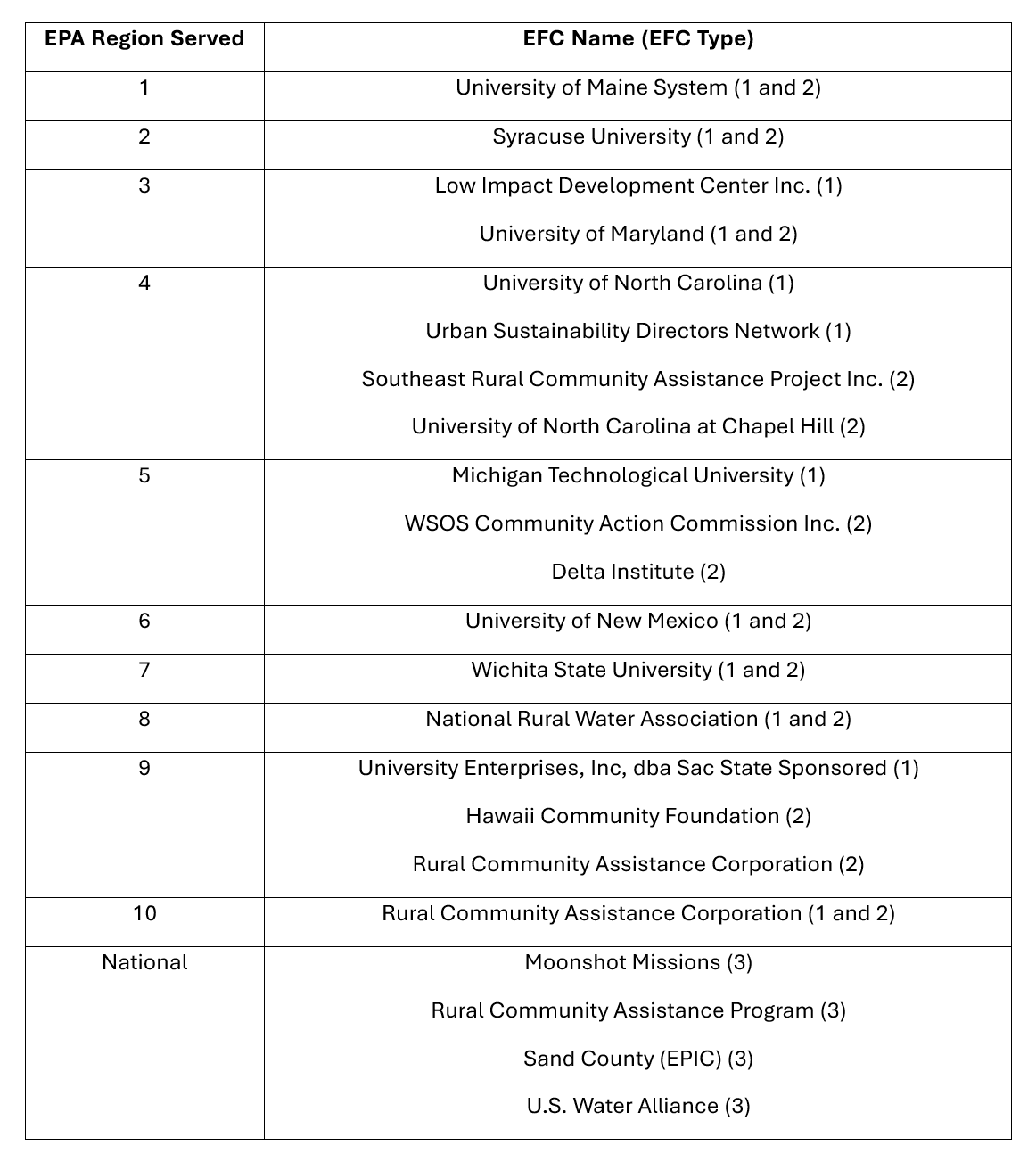

EPA divided the EFCs into three categories (Table 1). Two are partitioned by the EPA region they serve, the Regional Multi-Environmental Media EFCs (1) and the Regional Water Infrastructure EFCs with Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Funding (2), and one encapsulating national water infrastructure financing (3). All of these organizations are directed toward aiding underserved communities with project proposals, in addition to helping state, local, and Tribal governments stand up their technical assistance services.

Table 1: Environmental Finance Centers by EPA Region Served

Source: Environmental Protection Agency.

The structure of the programming is very targeted. EPA states clearly that existing environmental benefits and future progress cannot be adequately and equitably cemented unless localized entities can reliably access resources for environmental projects, including water infrastructure projects. The EFC grant program also names target federal funding programs, the State Revolving Funds and the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, that contain enormous funding opportunities for underserved communities.

Through IIJA and IRA, federal agencies have begun to make concentrated efforts at rebuilding and bolstering local administrative bureaucracies. It is possible that some states may have been awarded more federal funding or have implemented State Revolving Fund dollars more quickly because of their relatively more adept or strongly funded agencies — nationwide variations in funding results is viewable on the Water Program Portal’s Outcomes Dashboard.

A portion of EPA’s selected EFCs have collaborated to form the Environmental Finance Center Network (EFCN). Comprised of universities and non-profit organizations, the EFCs work together nationwide (and independently within their own regions) to expand access to trainings and resources. The EFCN also has published a funding table map, encapsulating all 50 states, six territories, and the Navajo Nation. Crosscutting initiatives aim to establish sufficient community capacity for water projects and for applying to water projects. In this way, the EFCN has taken a socially and geographically holistic approach to strengthen communities’ abilities to access crucial capital improvement funds, using federal funding as its launchpad.