On July 29, an 8.8 magnitude earthquake rumbled off the eastern coast of Russia. It sent a wave of tsunami warnings — indicating dangerous coastal flooding and potentially powerful currents — to states in the West, the most serious of which were in California and Hawaii. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Pacific Tsunami Warning Center eventually downgraded the alert to a tsunami advisory — indicating strong currents and waves dangerous to those in or very near to the water — early on July 30. Hawaii Governor Josh Green said at a press conference, as reported by the Honolulu Civil Beat, that the state coordinated between levels of government and activated hospitals statewide. A Hawai’i National Guard official noted that each county’s Emergency Operations Center had National Guard members positioned to anticipate local needs as they arose. Evacuation centers popped up as residents moved inland and to higher ground.

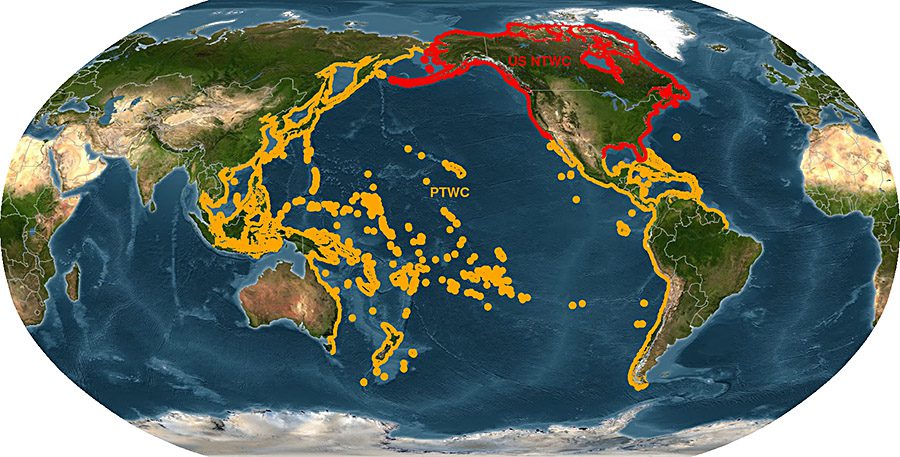

The data used to determine whether advisories or warnings are necessary for coastal communities in the event of tsunami potential are collected by a wide framework managed by NOAA. The U.S. Tsunami Warning System is geographically divided into two arms, the National Tsunami Warning Center and the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center. The National Center alerts the continental U.S., Alaska, and Canada to potential dangers while the Pacific Center provides warning messages for the British Virgin Islands in addition to American territories in the Caribbean and Pacific, as well as Hawaii and countries in Oceania and Asia (Figure 1).

Figure 1: U.S. Tsunami Warning Centers

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | Coverage areas for the U.S. tsunami warning centers: National Tsunami Warning Center (red) and Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (yellow).

Both centers are staffed 24/7, ready to analyze incoming readings to accurately and efficiently send out tsunami warnings when necessary. To collect this data, seismic stations are sited internationally to detect the movement of the ground. Seismic waves travel at paces much faster than tsunamis. As a result, scientists can predict the severity of a potential tsunami based on the seismic movement detected before a massive wave gets close to land. In fact, they are often able to issue the appropriate warning within five minutes of a quake.

If a center believes that an earthquake is powerful enough to trigger a tsunami, they will also refer to data from their water-level networks, comprised of buoys from the Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami (DART) system. The buoys can detect pressure changes by translating water-level height — essentially, as water height increases, water depth increases and pressure increases, making a tsunami more powerful. NOAA also has a network of water-level stations on the coasts to take stock of the ocean’s height at particular locations. These systems record the height of the tides to validate when a tsunami arrives and the height of its waves.

This data is crucial to collect for the safety of communities impacted by climate change nationwide. Investment is required to maintain and modernize this data infrastructure. Most recently, new funding was provided by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). $30 million from IIJA’s Ocean and Coastal Observing Systems – National Weather Service program was awarded to the Science Applications International Corporation to upgrade DART’s tsunami detection and warning capabilities specifically in May 2024. Also through IIJA, NOAA was awarded $26 million in October 2023 for the a pilot program improving early warning for natural disasters including flooding and fires in the Upper Missouri River Basin.

In an era of escalating climatic conditions — both scientifically forecasted and spontaneous, like earthquakes — ensuring the strength of monitoring and alert systems is crucial. For instance, in the case of the Texas floods this July, the data collected by NOAA was strong, but the local warning systems were not able to efficiently alert communities. Accurate and efficient information dissemination from officials is a keystone component of disaster mitigation and adaptation, and investments like those from IIJA help to bolster our disaster response efforts.