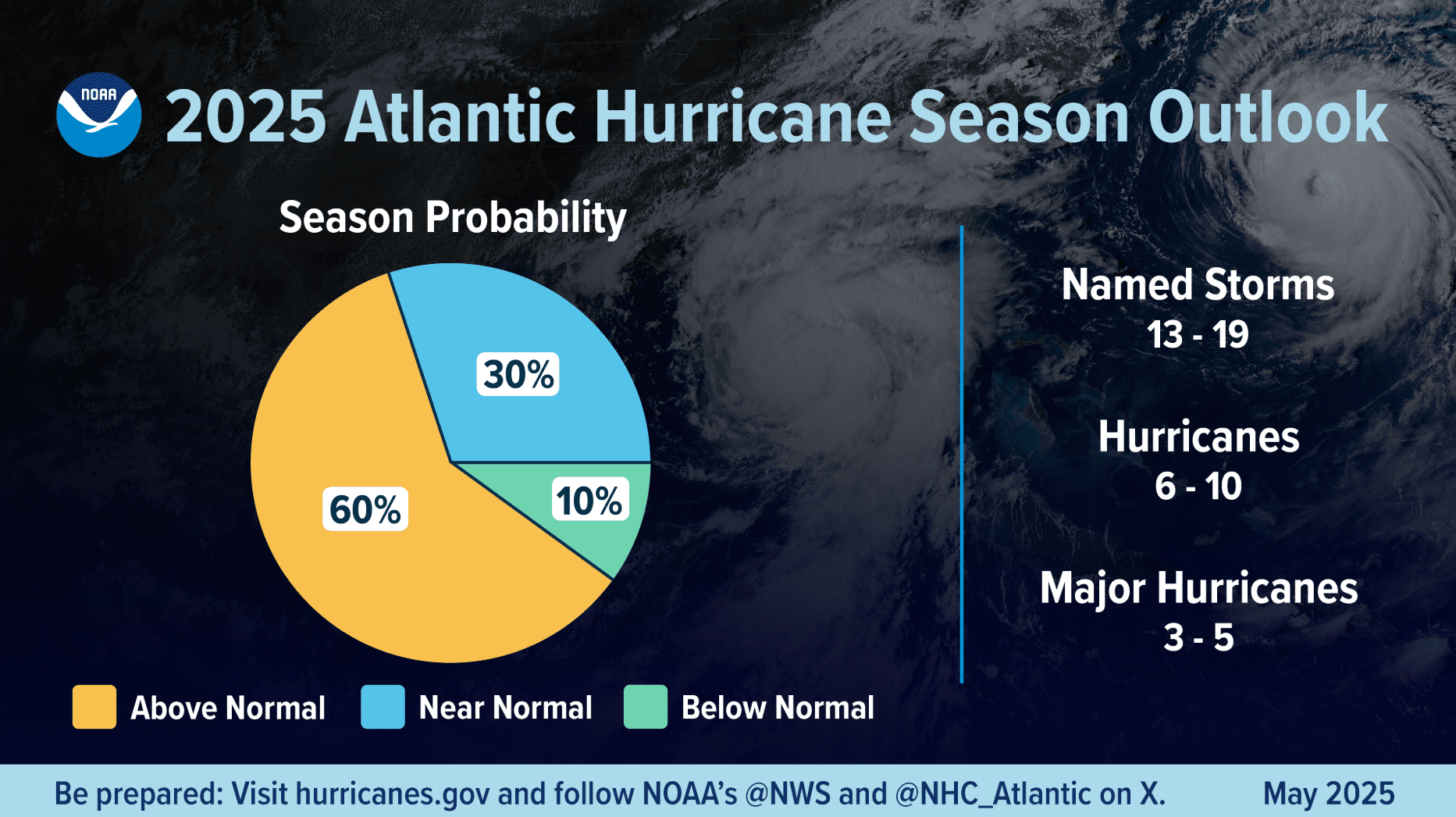

On May 22, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its forecast for this year’s Atlantic hurricane season, indicating a 60 percent chance of above-normal activity. Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 through November 30, and NOAA predicts between 13 and 19 named storms in 2025 (Figure 1). This volume of extreme weather may spell trouble for both the agency threatened with defunding amid budget reconciliation and the hurricane-threatened states taking up the mantle of disaster mitigation and response.

Figure 1: NOAA’s 2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook

Source: NOAA.

In the agency’s press release, NOAA indicated that warmer ocean temperatures, potentially higher activity from the West African Monsoon (one of the primary starting points for hurricanes in the Atlantic), and weak wind shear are contributing factors to the likely above-average activity, which may result in as many as five major hurricanes. Further, the press release highlighted NOAA’s National Weather Service Director Ken Graham’s nod to “more advanced models and warning systems in place” that have aided them in making this determination. Additional forecasting upgrades and communication enhancements will also be rolled out this year, including an update to the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System and investments into the National Hurricane Center and Central Pacific Hurricane Center.

Changes Brewing at FEMA and NOAA

The Atlantic hurricane forecast comes at an adverse moment for the agencies in charge of predicting and responding to disasters, NOAA and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Acting FEMA Administrator David Richardson — an ex-Department of Homeland Security official with no disaster management experience who was appointed in early May — perhaps jokingly commented to staffers that he was not aware the U.S. had a hurricane season. Around 2,000 FEMA staff and 2,400 NOAA staff have departed the agencies since the beginning of the Trump Administration. On May 8, NOAA said that it would halt tracking of natural disasters caused by climate change, namely ending updates to its Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters database; the database persists in an archived form, with data from 1980 to 2024. On top of all that, no FEMA officials were present at NOAA’s hurricane forecast announcement, signaling a tonal shift.

Budget reconciliation has only further shown how operations may become more strained at the two agencies. A recent Water Program Portal Spotlight Story highlights how the House budget reconciliation bill proposes the diversion of almost $2.9 billion in FEMA funding to the State Homeland Security Grant Program and residential protection for President Trump. On NOAA’s side, the bill targets $2.8 billion in unobligated Inflation Reduction Act funding are being targeted. Additionally, FEMA canceled the Building Resilient Infrastructure Communities program, rescinding $882 million in funding meant to bolster resilience to hurricanes.

Last week, NOAA announced that it would be hiring ahead of hurricane season, beginning with 126 employees to “stabilize” the National Weather Service. Despite these political changes, officials from both agencies have publicly stated that they are prepared for Atlantic hurricane season.

New State-Level Responsibilities

Most of the cuts at NOAA aim to shift the agency’s focus from climate change and equity. FEMA’s changes, however, are concerned with transferring responsibilities for disaster response, mitigation, and management from the federal government to the states. The states most likely to be severely impacted by Atlantic hurricane season include those along the Eastern Seaboard and the Gulf Coast, particularly, Florida, Texas, North Carolina, Louisiana, and South Carolina.

These states are all in different places financially and bureaucratically regarding their state-level disaster management. An AP News article calls out that larger staff with greater budgets and well-trained staff such as Florida and Texas will adapt well; others may not. The same can be said of states experiencing other kinds of natural disasters, like tornadoes and wildfires.

For instance, in late May, President Trump greenlit FEMA assistance for communities in eight states — Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Mississippi, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas — who had been waiting for months. The money will go toward recovery from severe storms in March. Kentucky, Missouri, and Oklahoma will likely soon have federal disaster requests pending from a slew of tornadoes and thunderstorms in mid-May.

When major disasters are federally declared, FEMA funds about three-quarters of the cost of disaster response statewide, while also funding the rebuilding efforts of individual communities. President Trump has denied half of submitted major disaster aid requests thus far under his tenure, often with little-to-no reasoning. Some state officials have simply come out and said it, such as Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear: they need federal support.

Of course, contrasting statements also exist, such as from Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. These shifts represent a sharp politicization of the science-based federal agencies that form the bedrock of domestic climate resilience. Without stronger guidance on how these responsibilities will be shifted to the state level, if at all, communities nationwide will remain vulnerable.