As federal agencies review their programs at the behest of the White House, awardees nationwide have reported halting and inconsistent access to federal dollars. Take, for instance, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) announcement from Monday, March 10th, that it had canceled over 400 grants from nine programs, resulting in a claw back of $1.7 billion in federal funding in the agency’s fourth round of award cuts. In the world of federal funding for water, many wastewater facilities and public water systems have been impacted by the uncertainty and confusion.

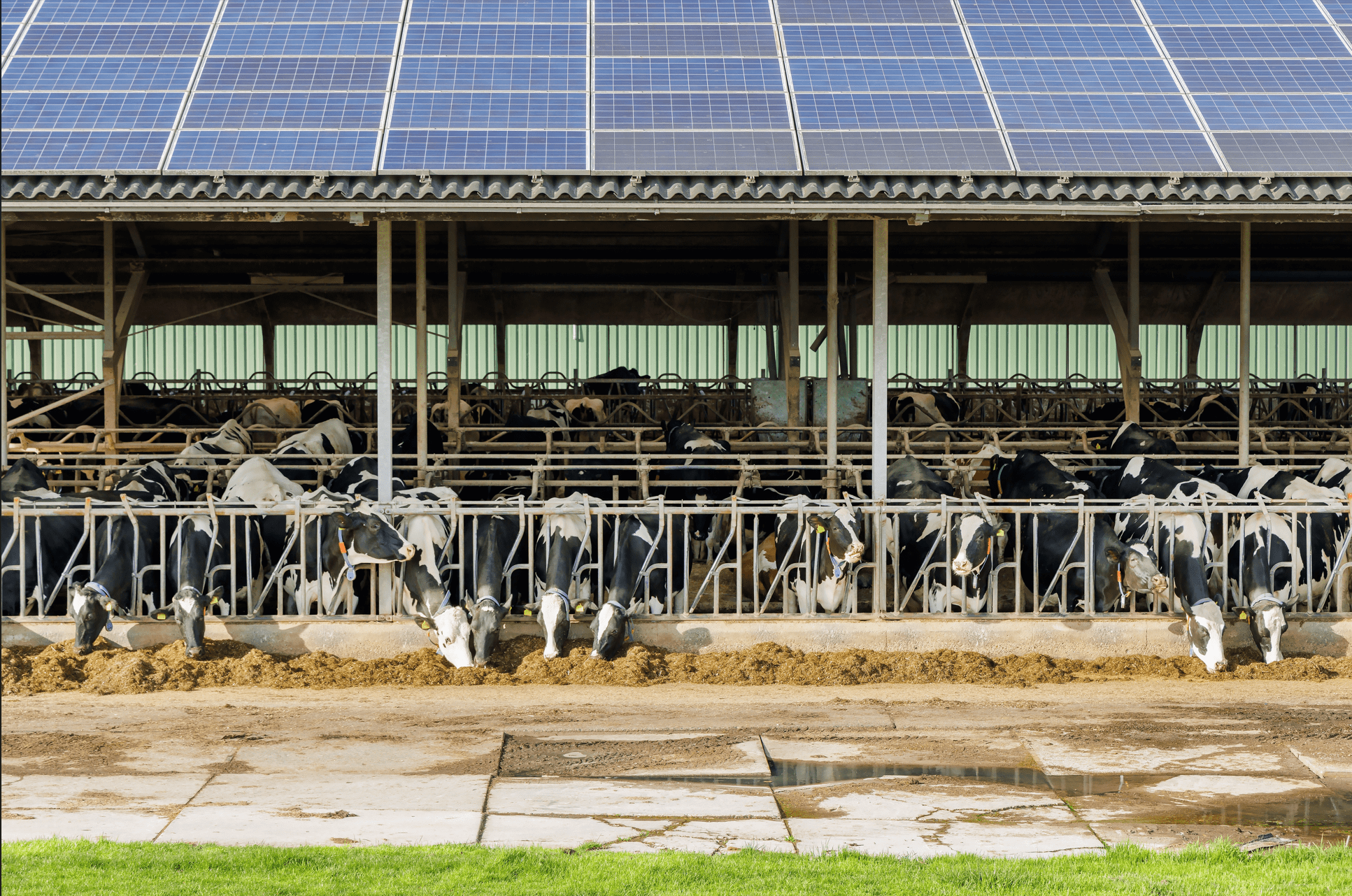

EPA did not clarify which nine of its programs the 400 grants stemmed from. One Inflation Reduction Act program that has experienced stop-and-start (and then stop) access to funding is EPA’s Community Change Grants program. Yet the non-profit awardees nationwide, including to residential wastewater treatments in Alabama and residential connection to sewer and water systems in Alaska, have reported an inability to access the federal government’s payment system or a clear designation in the system that their grant had been suspended.

The Community Change Grants are a likely target for the Trump administration’s EPA to slash, given the program’s environmental and climate justice focus. The program is funded through the Environmental Climate and Justice Block Grants, a $3 billion package of grants and technical assistance for implementing disadvantaged community-led projects related to air pollution and climate change. Of that $3 billion, about $2.3 billion has been awarded, of which about $1.6 billion has been distributed through the Community Change Grants in two rounds in 2024.

The program’s importance stems from the fact that its projects are community-centric and community-driven, all to the end of bolstering local climate resilience. Some of its awarded projects include a nature-based effort to ameliorate stormwater management in Tennessee and another to consolidate four water systems and a number of household wells to improve water quality in California; both projects were awarded $20 million. Both of these projects are very localized, addressing a particular issue by a particular water system. The pausing of this targeted program is a loss for local governments and utilities to independently improve their water quality.

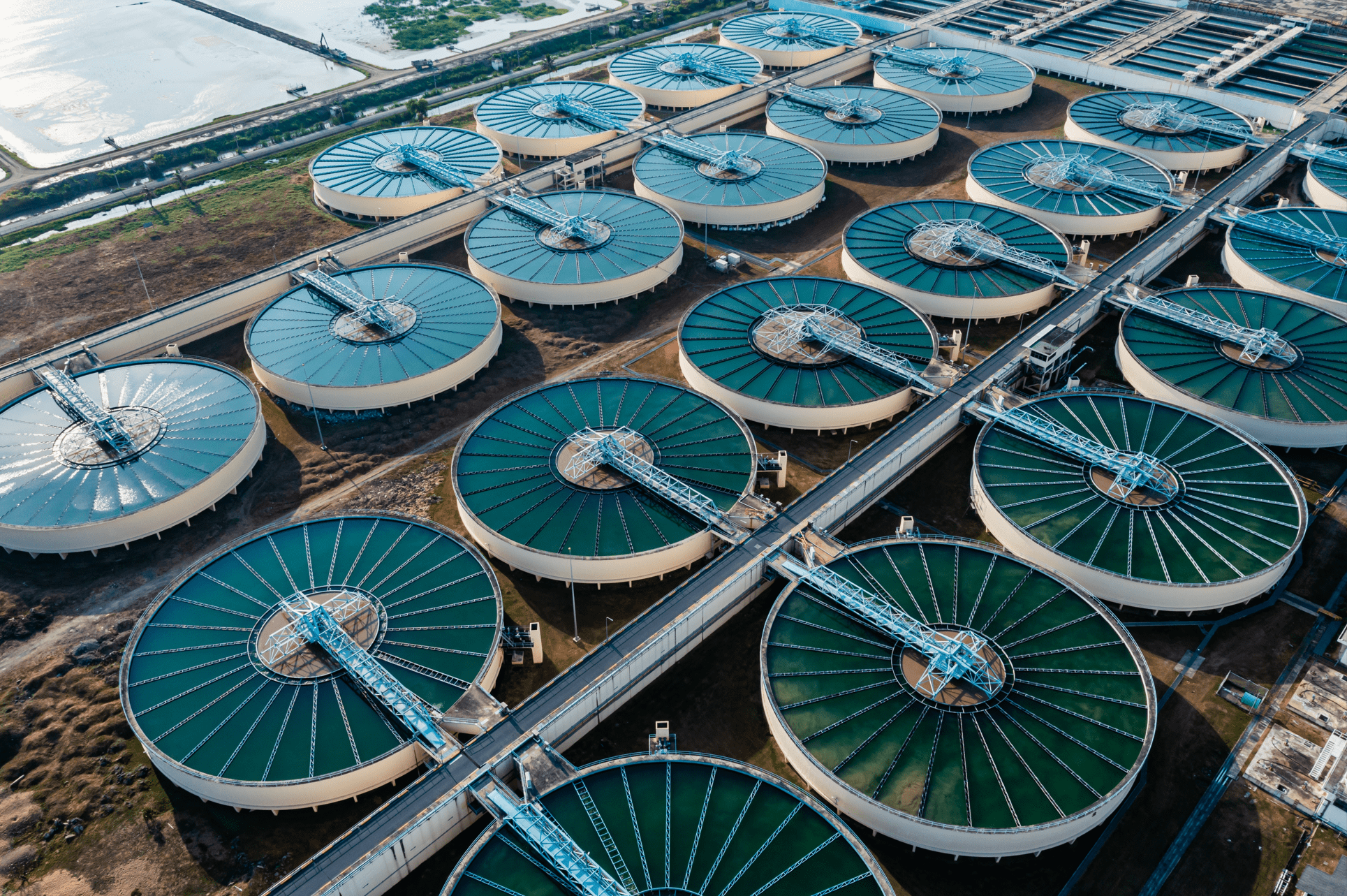

The same negative impact is elucidated from the general uncertainty from federal decisions and how they are impacting state decisions surrounding the State Revolving Loan Funds (SRFs). Recent reporting from Maine highlights how the stop-and-start flow of funding and information from federal authorities has made it harder for water utilities and wastewater facilities to continually maintain the state’s aging water systems.

The Maine Water Environment Association, representing 135 water districts, noted that their members rely on the SRFs low interest loans and federal five-to-one matching, while the Maine Water Utility Association, representing 400 water systems, expressed the importance of the SRFs in terms of not only consistent management of waste and contaminants like PFAS, but also for simple fixes that are always needed such as fixing water main breaks.

While the SRFs received substantial boosts in funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the programs’ year-on-year base appropriations have been decreasing — and is expected to continue decreasing. Without being able to count on stable financial support from the federal government, utilities’ are pushed to raise prices for consumers so that they may fund maintenance and management.

Some states have existing supportive programs to fill the federal funding gap, including the Decentralized Wastewater Treatment System Pilot Program in North Carolina. This program recently announced its inaugural awards totally over $265 million to 99 drinking and wastewater projects in the state. Projects endeavor to install new drinking water lines, connect residential units to larger water systems, and perform repairs and replacements for residential septic systems.

While state programs like North Carolina’s can help address some of the funding gaps facing local drinking and wastewater systems, America’s water infrastructure needs investment at the federal scale. Without a basis of federal funding acting as a safety net — a safety net that has largely historically been woven from SRF funding — then our drinking and wastewater infrastructure will continue to face greater risks of breakage and failure.