June heralded the beginning of the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season, which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Weather Service again predicts will have an “above-normal” amount of hurricane activity. The agency reports that the chance of above-normal activity is 85 percent. In total, NOAA is forecasting between 17 and 25 named storms, with four to seven having the potential to become major hurricanes.

This forecasted increase in activity is primarily due to the impending La Niña, which is expected by the middle of this hurricane season, and climate change. Generally, El Niño conditions drive strengthened hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific, while dampening hurricane activity in the Atlantic. La Niña does the opposite, reducing upper- and lower-level winds over the Atlantic, reducing vertical wind shear as well as atmospheric stability, and lending itself to a greater number of stronger hurricanes.

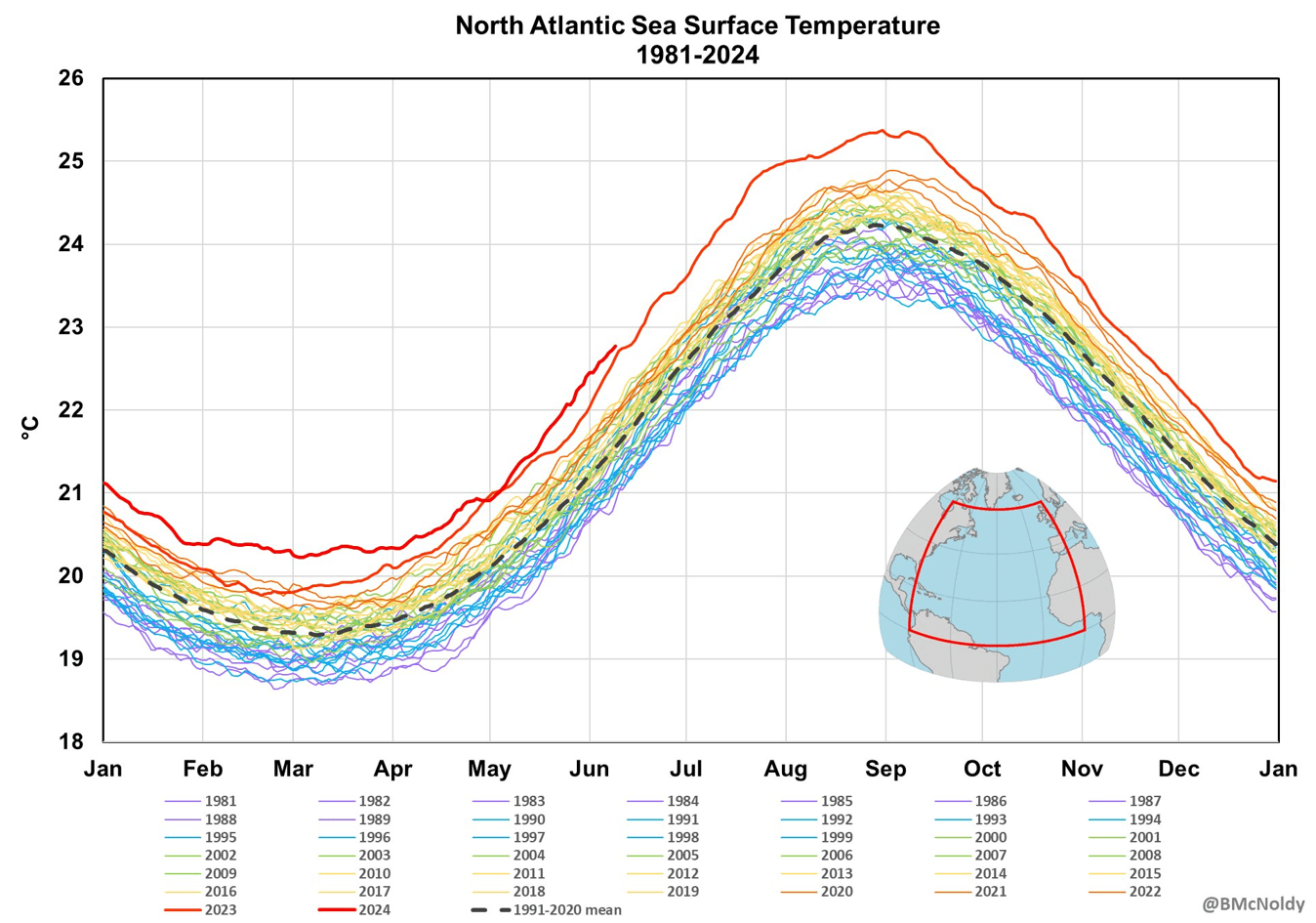

Further, the Atlantic is currently unseasonably warm. Ocean water temperatures have been hitting record levels of heat since March 2023, according to NOAA measurements of North Atlantic Sea surface temperature (Figure 1). In April 2024, average water surface temperatures were about two degrees higher than historical averages. Thus far in June, water temperatures are over 4 standard deviations above the mean from 1991-2020.

Figure 1: North Atlantic Sea surface temperatures, 1981-2024

Source: Brian McNoldy, Senior Research Associate at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School

NOAA’s National Weather Service and National Ocean Service rely on an in-depth system of observing equipment, forecasting models, and flood mapping tools to provide these outlooks and track storms. As a result, federal agencies can expediently report to emergency and water managers across the country and the public during extreme weather events. These technologies represent critical climate resilience tools as the Atlantic and Pacific continue to experience above-normal hurricane seasons.

Two programs embedded in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) feed funding to NOAA to bolster these systems — the $50 million Ocean and Coastal Observing Systems – National Weather Service program and the $100 million Ocean and Coastal Observing Systems – National Ocean Service program.

The National Weather Service program is focused on the longevity of two ocean observations systems: the Tropical Atmosphere Ocean (TAO) array in the Pacific and the Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami (DART) network. The TAO array was completed in 1984 and measures oceanic and surface variables related to climate events such as El Niño. The DART network, which was awarded $30 million last month, is made up of 39 buoys across the Pacific and Atlantic. Together, the buoys translate wave patterns and pressure readings from the ocean floor to predict tsunamis and alert potentially vulnerable coastal communities.

The National Ocean Service program, on the other hand, has a more distributed funding approach. Coastal, Great Lakes, and ocean observing systems will receive modernization and stabilization upgrades to the end of enabling effective reporting to coastal communities. These systems monitor extreme weather in addition to flooding, algal blooms, and other aquatic issues. Thus far, about $19 million has been awarded to the U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System, the Argo program, and the Surface Ocean CO2 Reference Observing Network.

These systems and others — including the IIJA-funded Flood Inundation Mapping system that launched this year — are pointed at the development of the New Blue Economy. As coined by NOAA, the knowledge-based ocean economy is necessary for coastal climate resilience and adaptation, particularly to support resource management.

As a result, their maintenance when pieces break and upgrading when more effective technologies arise are crucial. The TAO array was last redesigned and updated 30 years ago. Data dropouts on the DART network have historically occurred and recent updates to the DART buoys — to make them hardier so that reporting can occur faster — require additional funding like this May’s to roll out.

Establishing and adapting this oceanic observational infrastructure is the keystone to informing stewardship and maintaining coastal communities, where 40 percent of Americans reside, for decades to come.