Over 23 million households nationwide rely on groundwater wells as their source of water, as estimated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), amounting to about 15 percent of the population, or 43 million Americans. Yet, there is no solid federal source of data documenting the location and quality of these residential wells — a gap in data collection that new research is filling.

This year, several Virginia Tech researchers published the United States Groundwater Well Database (USGWD), the first unified and comprehensive database of groundwater wells — including residential, monitoring, irrigation, and other well use cases — compiled from state and federal agencies.

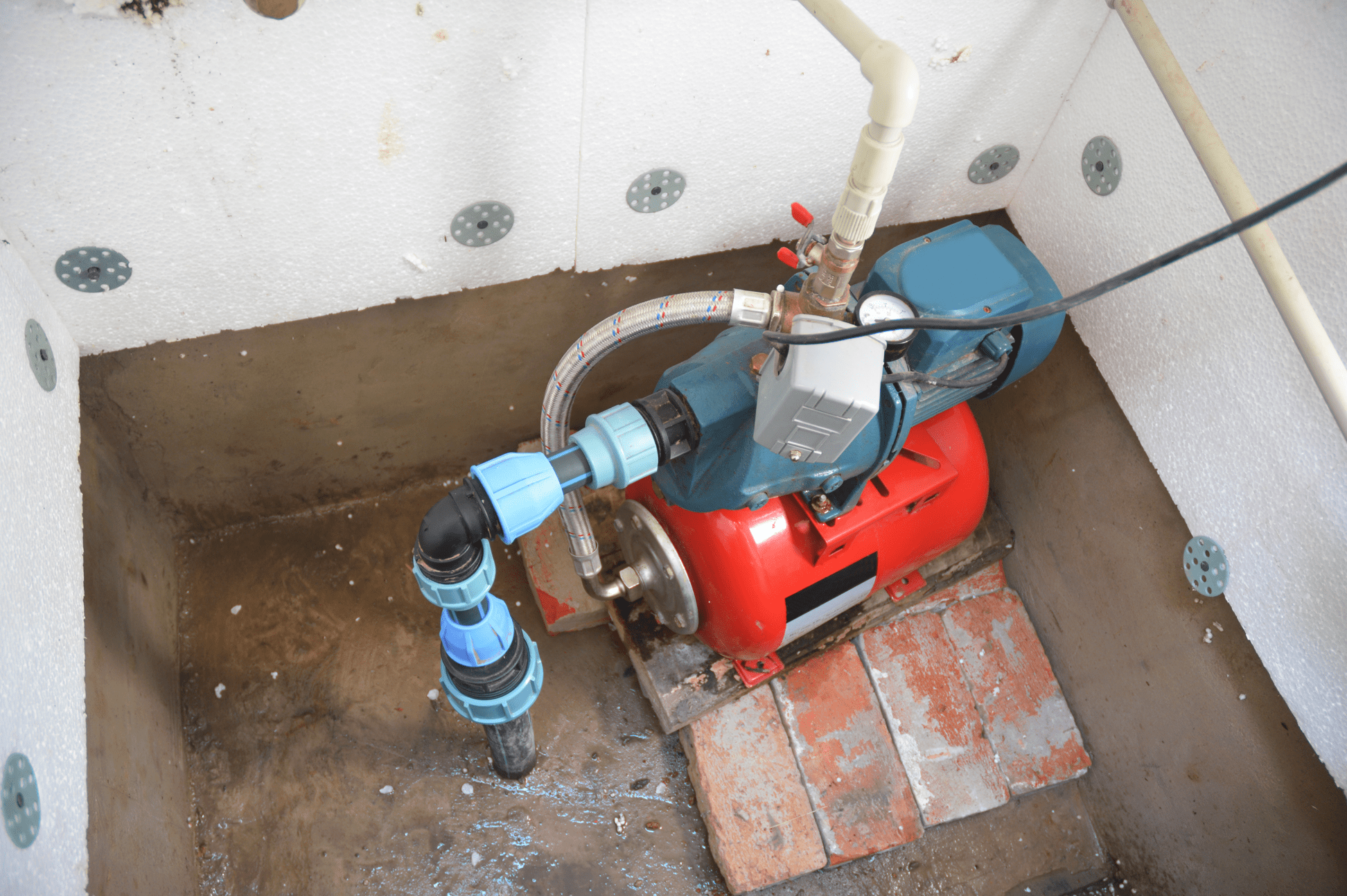

Wells are deep holes drilled into the ground to siphon water contained in aquifers. To draw this water to the surface, a pipe is fed down into the ground. A pump at the surface pulls this water up through screen filters, to remove debris, and out to where the water is needed. Depending on local hydrology, wells may be shallow, bored into unconfined water sources; consolidated, drilled into a natural rock formation that holds its shape; or unconsolidated, drilled into a sand, soil, gravel, or clay formation that collapses on itself when water is withdrawn.

The engineering of a well is complicated, requiring casing to prevent water leakage and knowledge of local terrain and potential contaminants that may endanger those using a well’s water. Further, if wells pump water faster than it is naturally replenished, the groundwater — its source — depletes. Eventually, wells may run dry as water level dips below its depth. Residential wells tend to be shallower than their industrial or agricultural counterparts, and consequently, are at greater risk of running dry. Groundwater depletion also causes reductions in surface water, subsidence, and a deterioration of water quality.

Given the significant portion of the population that relies on groundwater wells to stay hydrated, it is surprising that state data collection and reporting on these sources vary so much state by state. The report authors requested the well records of each and every state in the nation before cleaning and standardizing the data.

All in all, about 14.3 million wells were recorded. They found that while crop irrigation remains the largest user of groundwater, domestic wells overwhelm the database at about 6.8 million of the about 12.3 million recorded groundwater wells with locational data. The number of reported wells in each state varies dramatically, from over 1.1 million in California to 90 in New Hampshire. Furthermore, even in states with relatively high counts of wells — such as Ohio, Maryland, or Minnesota — data points often lack a reported county, never mind a set of specific coordinates. Also, many states lack data on whether the recorded wells are being actively used; in total, about 32 percent of the data sets’ wells were classified with unknown statuses.

The paper also identifies via spatial data the density of well records sited over aquifers nationwide, inferring which wells are drawing from which aquifers. This analysis can likely help estimate where wells may go dry and investments may be needed, which is particularly important given many residential wells are located in rural or historically disadvantaged areas. It can also help estimate where groundwater is at risk of being over-tapped.

Four programs tracked on the Water Program Portal and funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs ACT (IIJA) contain funding focused on maintaining and developing groundwater resources: the Enhanced Aquifer Use and Recharge, Pilot Program for Alternative Water Source Projects, Water & Groundwater Storage and Conveyance, and Water Recycling programs, totaling $2.3 billion. Three are focused on the deployment of groundwater resources, while the Enhanced Aquifer Use and Recharge program is dedicated to researching aquifers’ resources.

The federal agencies housing these programs — the Department of the Interior for the Water & Groundwater Storage and Conveyance ($1.15 billion) and the Water Recycling ($1 billion) programs, and the EPA for the Enhanced Aquifer Use ($25 million) and Recharge and Pilot Program for Alternative Water Source Projects ($125 million) programs — may leverage this research and its resulting data tool to properly scope and direct funding for areas whose are either underreported or at risk of running dry. The National Groundwater Association, the Groundwater Foundation’s Water Well Wish program, and members of the US Water Alliance or the Water Equity Network may also use this data to focus and advance their work.