Every method of fossil fuel or mineral extraction leaves behind industrial and chemical evidence. Orphaned gas and oil wells leave toxic trails of leaky pipes penetrating deep into the earth and sticking out of landscapes across the country. Similarly, abandoned mines contaminate or scar the land and water they are sited around.

The Infrastructure Investment Jobs Act (IIJA) injected $11.293 billion — to be distributed as about $725 million annually over 15 years — to shutter mine shafts and clean up acid mine drainage, thus restoring damaged water supplies. The Abandoned Mine Reclamation Fund, one of the largest programs on the Water Program Portal, feeds the existing Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Program run by the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE), and is available to 22 states and the Navajo Nation

In 2020, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that at least 140,000 abandoned hardrock mines or mine features were identified by federal agencies OSMRE currently reports over 246,000 closed or abandoned mines in its National Mine Map Repository, some as old as the 1790s; these may cover more than 850,000 acres. An additional 400,000 are estimated to remain on federal land but have not been identified.

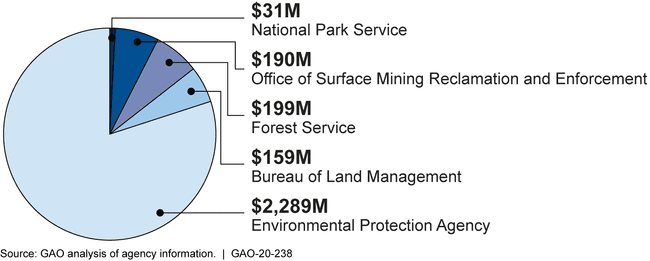

Lack of funding is the largest limiting factor for abandoned mine clean up, according to GAO. Historically, about $3 billion (Figure 1) was spent by the federal government between 2008 and 2017 on abandoned hardrock mine clean up, with an average of $287 million spent per fiscal year. IIJA nearly tripled that commitment, representing a significant increase in federal spending.

Figure 1: Federal Expenditures to Address Abandoned Hardrock Mines by Agency, Fiscal Years 2008-2017 (Nominal Dollars)

According to OSMRE, remediating a single mine can dramatically range in cost, between tens of thousands to tens of millions. This wide range exists because, in addition to the ecological and human health risks associated with their clean up, the cultural or historical significance of these mines must also be contended with.

Despite the costs, remediating these lands is critical to maintaining water quality. Rain, groundwater, or water used in mining (especially for mineral processing) becomes more acidic as heavy metals and in the rock leach out. When chemical agents are used for processing, they also become potential environmental contaminants. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, wastewater from mining affects over 10,000 miles of American waters, largely due to acidic runoff. Any of this acid runoff also threatens to contaminate groundwater or toxify aquifers. Wastewater may also be extremely salty, representing another source of pollution. Luckily, once remediation is completed, land and water conditions are often restored to their quality before the area was ever mined.

The remediation of lands and waters contaminated by orphaned oils is largely politically framed as a public and ecosystem health issue, but this work also generate economic benefits. Restored lands can again host economic redevelopment projects. Interestingly, while the environmental impacts of leaving abandoned mines to fallow are clear, the Biden administration is framing this redevelopment as an economic necessity and creating programs to support the generation of economic benefits.

For instance, the Clean Energy Demonstration Program on Current and Former Mine Land is deploying $500 million to “demonstrate innovative mine land conversion” with clean energy projects, including energy storage, renewable energy like solar and geothermal, and fossil fuel-burning projects paired with carbon capture. This initiative supports the AML Program bolsters the clean economy transition in employing incumbent energy workers in climate-friendly sectors.

The economic ripples of the AML Program are encouraging, and the AML Program is also being implemented in accordance with the Justice40 Initiative making the climate-friendly economic transitions in these historically disadvantaged communities even more significant.

Funding that these states are eligible for varies based on amount of existing damage and effectiveness of state applications. Almost $245 million is available for Pennsylvania and about $141 million is available for West Virginia, compared to under $2 million for Alaska, Arkansas, the Navajo Nation, and Texas, respectively. States with higher concentrations of AMLs —particularly across Appalachia, where 84 percent of AMLs lie — are already receiving the highest proportion of funding to speed these communities’ ecological and economic revitalization.