Water rights in the West today are based on historical usage of water sources, known as the prior appropriation doctrine. Indigenous communities ironically hold a very weak stake when it comes to these rights, considering that they are the only people native to this land.

The basis of the majority’s opinion in Arizona v. Navajo Nation rests on a peace treaty signed in 1868. The treaty established the boundaries of the Navajo Reservation and detailed the education of Navajo children, while ceasing the war between the Navajo and the US and permitting railroad construction through Navajo lands. It also reserved “necessary water” for the reservation, while — importantly to the Supreme Court — not asserting that the federal government had to take any further steps to secure access to water for the Navajo Nation.

Access to water in the West is, and likely always will be, contentious and competitive. The Navajo source their water from the Colorado River; as do states like Arizona, Nevada, and California. The Navajo Nation sued several federal agencies under the National Environmental Policy Act due to their overlooking of Navajo water needs during their management of the river’s water in 2003, creating the basis for this Supreme Court case.

In Arizona v. Navajo Nation, the Navajo specifically were inquiring how much water they should have the right to access, as the 1868 treaty did not include even a broad estimate. By asserting that the treaty did not and does not require the federal government to assess or secure that volume — they have no “affirmative duty” — Arizona et al. won the majority of the Court over.

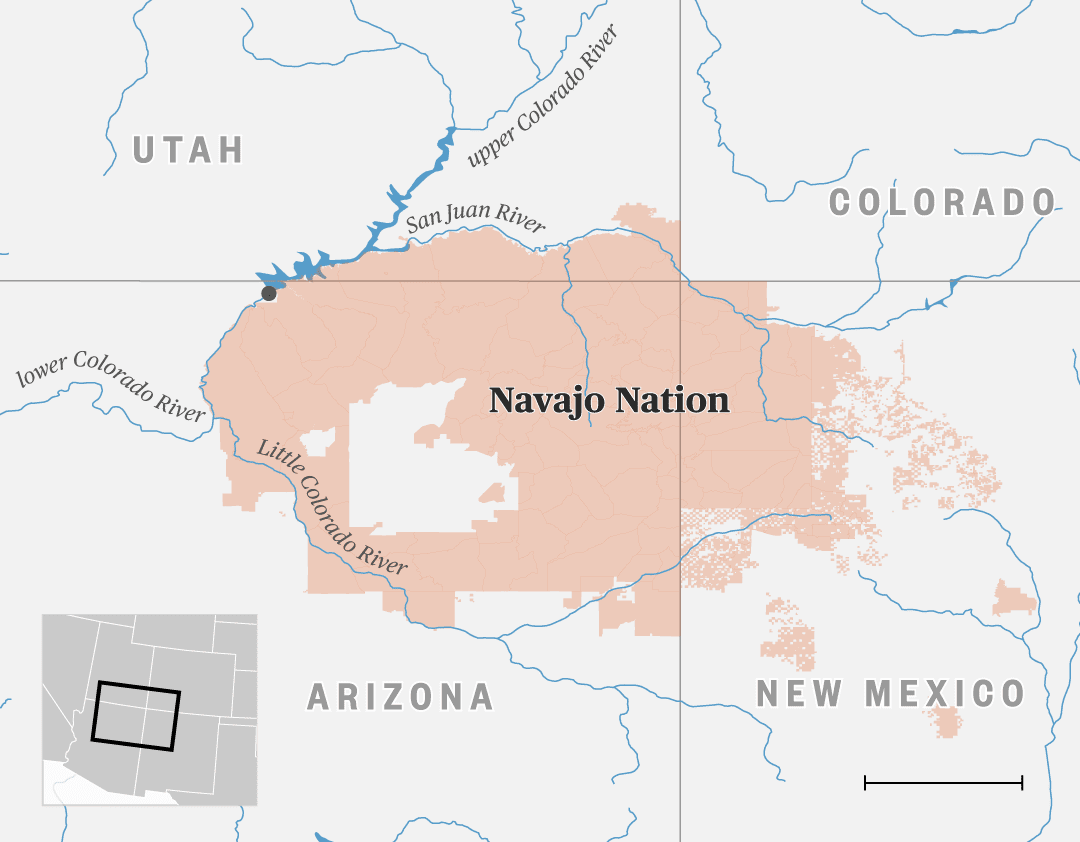

Figure 1: Map of the Navajo Reservation

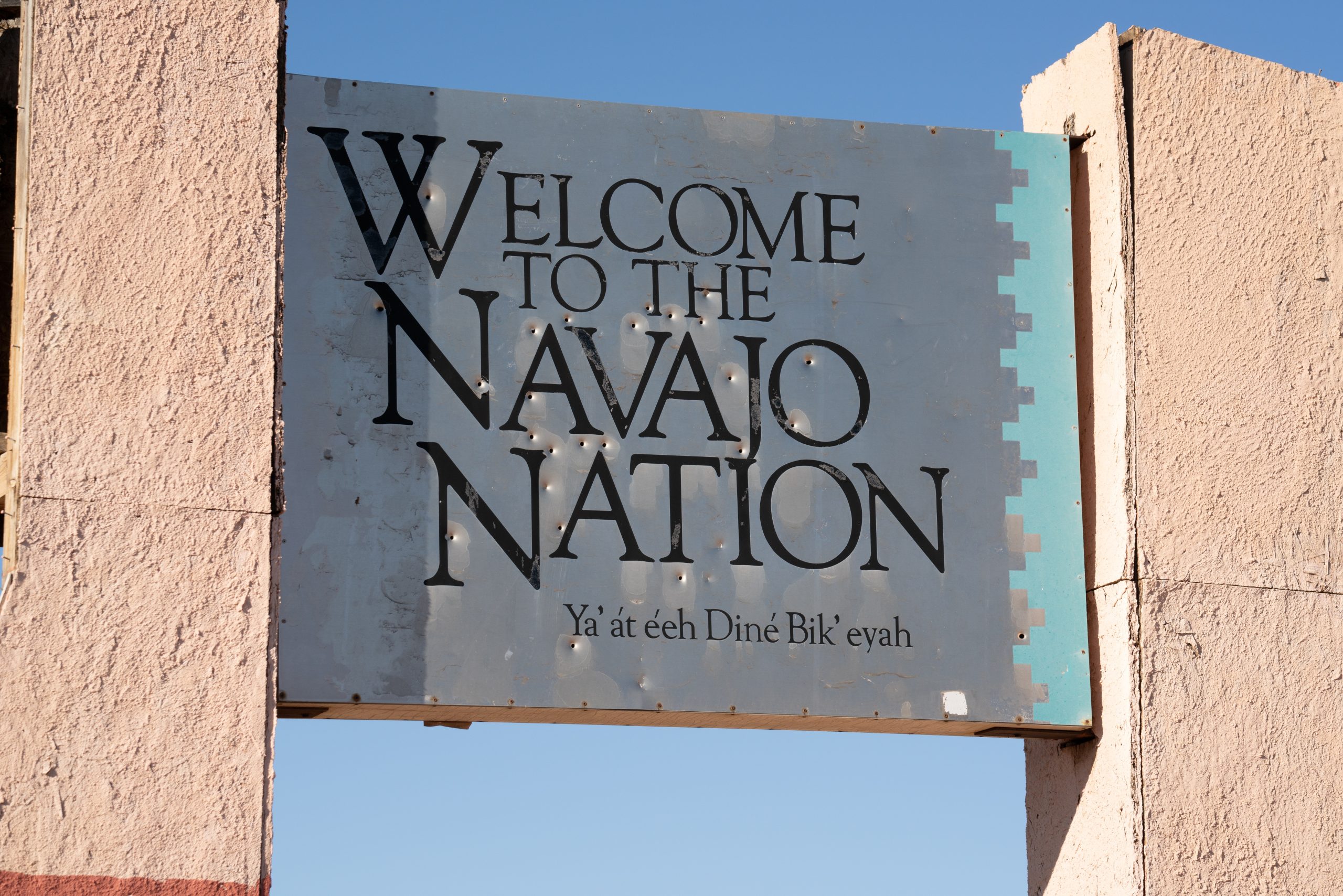

For Indigenous communities, the ruling was disappointing but expected. The 17-million-acre reservation is home to almost 300,000 American citizens and stretches across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. The Colorado River runs along the northwest edge of the reservation. According to the Navajo Water Project, 30 percent of Navajo Nation families live without running water — a proportion that would never be experienced in a state — instead hauling barrels periodically to wells in order to drink, cook, and bathe.

Funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) recognizes this disparity, a baby step being taken by the federal government to address it. IRA’s Tribal Climate Resilience program, earmarked for $225 million, is one funding source the Navajo Nation and other Tribal governments may consider applying for to strengthen local source of drinking water. $12.5 million in the Emergency Drought Relief for Tribes block grant program may serve as a final stopgap in worst case scenarios.

Within IIJA, the largest Tribal Nation-focused pot of funding is the $2.5 billion Indian Water Rights Settlement Completion Fund. The bill text notes that dollar transfers can only occur for obligations under “an Indian water settlement approved and authorized by an Act of Congress” before IIJA was enacted. Essentially, the program is meant to fulfill languishing promises to supply water by the federal government; $580 million was allocated in February of this year, with over $178 million awarded to the Navajo Nation.

The Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) also continue to be keystones in enshrining safe and resilient sources of water across the nation, including in Tribal Nations. In fiscal year 2023, $15,515,000 was set aside for tribes in the CWSRF, while about $54.4 million was set aside in the DWSRF (note that these figures are for the base and general supplemental programs, not the Emerging Contaminants or Lead Service Line Replacement Supplemental Programs).

Other paths toward water justice for the Navajo Nation include continuing to push the issue legislatively and judicially. Agreements between the state of Arizona and the Navajo have been pursued over the past twenty years; none have panned out. Democratic governor Katie Hobbs may put this discussion back on the table given her campaign promises. Without that opportunity for discussion, a water adjudication case that has been languishing in Arizona’s court system since 1978 is the Navajo’s only thin hope.

Despite federal and state government funding efforts as well as repeated judicial pushes by the Navajo, they fall short of meeting Indigenous communities’ water needs. In his dissent for Arizona v. Navajo Nation, Justice Neil Gorsuch highlighted the fact that the Navajo have chased myriad pathways towards securing their water rights, to no avail. Time will tell how much empathy and urgency authorities will put into responding to this crisis of access in tribal nations.